Billie Swalla, UW Biology Professor, was quoted in Scientific American on Oikopleura, a group of organisms that discard genes to make a better heart.

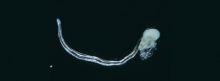

As far as sea squirts and their close relatives go, the genus Oikopleura represents a decidedly strange group of organisms, both from the standpoint of physical attributes and genetics. It belongs to a larger group of invertebrate animals that are closely related to all vertebrates: the tunicates. But unlike most others in that group, it does not undergo metamorphosis from a free-swimming larva to a fixed-to-the-bottom, or sessile, adult. Instead it lives its entire life as a tiny free-swimming creature, and it does so inside a balloon made up of a transparent sheet of cellulose, the main constituent of plants’ cell walls. The transparent balloon is its “house,” or “oikos” in Greek, and it envelops the entire body (about 0.5 millimeter in length) except for its long, extended tail, which beats continuously. Using its tail and heart to pump water through the semi-permeable balloon, Oikopleura filters small organic particles in the water and funnels any of this catch to its mouth.

The vast majority of adult tunicates sit on the bottom of the ocean and pump water into their mouth to filter feed; they do not come with a food-collection apparatus outside the body. But the free-swimming Oikopleura evolved a different way to filter feed. It is so small that it has to make a big balloon or fishing net outside of its body to capture enough food to meet its metabolic demands. This structure enables the animal to thrive as a free-swimming filter feeder. “It is absolutely crazy,” says Billie Swalla, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Washington, commenting on Oikopleura’s large, external food-collecting apparatus. Swalla studies the evolution of chordates, the phylum that includes both vertebrates and tunicates.

In the case of Oikopleura, the creatures’ house quickly gets gummed up with particles from the seawater, at which point the animals sheds their messy oikos. “So they don’t clean the houses. They make a new one. That is happening every three hours,” says Cristian Cañestro, an evolutionary developmental biologist in Barcelona. The abandoned houses blanket the bottom of the world’s oceans like white snow.

Read the full article in Scientific American.