Adam Summers, UW Biology Professor, was featured in UW News for new research about how shark intestines function. The research team from California State University, Dominguez Hills, the University of Washington and University of California, Irvine, published its findings July 21 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Contrary to what popular media portrays, we actually don’t know much about what sharks eat. Even less is known about how they digest their food, and the role they play in the larger ocean ecosystem.

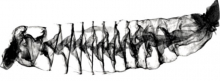

For more than a century, researchers have relied on flat sketches of sharks’ digestive systems to discern how they function — and how what they eat and excrete impacts other species in the ocean. Now, researchers have produced a series of high-resolution, 3D scans of intestines from nearly three dozen shark species that will advance the understanding of how sharks eat and digest their food.

“It’s high time that some modern technology was used to look at these really amazing spiral intestines of sharks,” said lead author Samantha Leigh, assistant professor at California State University, Dominguez Hills. “We developed a new method to digitally scan these tissues and now can look at the soft tissues in such great detail without having to slice into them.”

The researchers primarily used a computerized tomography (CT) scanner at the UW’s Friday Harbor Laboratories to create 3D images of shark intestines, which came from specimens preserved at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. The machine works like a standard CT scanner used in hospitals: A series of X-ray images is taken from different angles, then combined using computer processing to create three-dimensional images. This allows researchers to see the complexities of a shark intestine without having to dissect or disturb it.

“CT scanning is one of the only ways to understand the shape of shark intestines in three dimensions,” said co-author Adam Summers, a professor based at UW Friday Harbor Labs who has led a worldwide effort to scan the skeletons of fishes and other vertebrate animals. “Intestines are so complex, with so many overlapping layers, that dissection destroys the context and connectivity of the tissue. It would be like trying to understand what was reported in a newspaper by taking scissors to a rolled-up copy. The story just won’t hang together.”

From their scans, the researchers discovered several new aspects about how shark intestines function. It appears these spiral-shaped organs slow the movement of food and direct it downward through the gut, relying on gravity in addition to peristalsis, the rhythmic contraction of the gut’s smooth muscle. Its function resembles the one-way valve designed by Nikola Tesla more than a century ago that allows fluid to flow in one direction, without backflow or assistance from any moving parts (watch a video of how the Tesla valve works).

Read the full article on UW News.

Bonus: See related story in ZME Science.