When paleontologists at the University of Washington cut into the fossilized jaw of a distant mammal relative, they got more than they bargained for — more teeth, to be specific.

As they report in a letter published Dec. 8 in the Journal of the American Medical Association Oncology, the team discovered evidence that the extinct species harbored a benign tumor made up of miniature, tooth-like structures. Known as a compound odontoma, this type of tumor is common to mammals today. But this animal lived 255 million years ago, before mammals even existed.

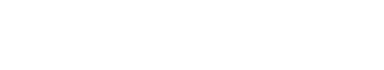

A histological thin section of the gorgonopsid lower jaw, taken near the top of the canine root. The dark area on the right is bone. The backward C-shaped structure on the left is the canine root. The cluster of small circles resemble miniature teeth, indicative of compound odontoma.Megan Whitney/Christian Sidor/University of Washington

“We think this is by far the oldest known instance of a compound odontoma,” said senior author Christian Sidor, a UW professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. “It would indicate that this is an ancient type of tumor.”

Before this discovery, the earliest known evidence of odontomas came from Ice Age-era fossils.

“Until now, the earliest known occurrence of this tumor was about one million years ago, in fossil mammals,” said Judy Skog, program director in the National Science Foundation‘s Division of Earth Sciences, which funded the research. “These researchers have found an example in the ancestors of mammals that lived 255 million years ago. The discovery suggests that the suspected cause of an odontoma isn’t tied solely to traits in modern species, as had been thought.”

“Most synapsids are extinct, and we — that is, mammals — are their only living descendants,” said Megan Whitney, lead author and UW biology graduate student. “To understand when and how our mammalian features evolved, we have to study fossils of synapsids like the gorgonopsians.”

“Most reptiles alive today fuse their teeth directly to the jawbone,” said Whitney. “But mammals do not: We use tough, but flexible, string-like tissues to hold teeth in their sockets. And I wanted to know if the same was true for gorgonopsians.”Paleontologists have categorized many “mammal-like” features of gorgonopsians. For example, like us, they have teeth differentiated for specialized purposes. But Whitney started studying gorgonopsian teeth to see if they had another mammalian feature.

Read full article in UW Today.

Other news: National Science Foundation