Think of them as extra-large parasites.

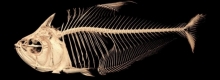

A small group of fishes — possibly the world’s cleverest carnivorous grazers — feeds on the scales of other fish in the tropics. The different species’ approach differs: some ram their blunt noses into the sides of other fish to prey upon sloughed-off scales, while others open their jaws to gargantuan widths to pry scales off with their teeth.

A team led by biologists at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories is trying to understand these scale-feeding fish and how this odd diet influences their body evolution and behavior. The researchers published their results Jan. 17 in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

“We were expecting that with this specialized scale-eating niche, you would get specialized morphology. Instead, what you get is a mosaic of strategies for the end goal of scale feeding,” said lead author Matthew Kolmann, a postdoctoral researcher at Friday Harbor Laboratories.

“This niche has a hidden complexity to it, and it is yet another story about the incredible diversity of life on Earth.”

The researchers compared two species of piranha fish — one that feeds on scales only as a juvenile and another that eats scales its whole life — and two species of characin fish, commonly known as tetras, with similar eating habits as the piranhas. They found that all four of the scale-feeders varied considerably in their body shape and feeding strategy.

The piranha that eats scales its whole life, named Catoprion mento, tends to live alone. When it does hunt, it swims up behind its prey, opens its large, Jay Leno-like jaw 120 degrees and pries large scales off the sides of other fishes. These piranhas can tolerate nearly a dozen large fish scales in their stomachs at one time; that’s like a human swallowing a dozen silver dollar pancakes in a single bite.

In contrast, the characin fish most similar to the piranha in life history and eating preferences gets its food in an entirely different way. The blunt-faced fish, called Roeboides affinis, has teeth on its nose and butts its face into other fish, devouring the scales as they fly off from the force of impact.

“Roeboides is like a car that intentionally runs a stop sign and t-bones another car — then picks up the tail lights and window trim knocked off in the crash. It is a crazy strategy,” said co-author Adam Summers, a professor of aquatic and fishery sciences and of biology at Friday Harbor Laboratories.

Read the whole article on UW Today.